Translation: Jesusa Laparra (1820-1887)

Here’s another chapter of my thesis. I hope someone enjoys this or finds it useful! Someday I’d love to spend a few years traveling around to different libraries in Spanish America looking up old issues of these journals, finding and collecting and translating poems.

Jesusa Laparra (1820-1887)

Jesusa Laparra and her sister Vicenta, originally from Guatemala, founded and edited a women’s journal, La Voz de la Mujer, in the mid-19th century; started a literary magazine, El Ideal; and wrote for other progressive and feminist journals. Jesusa wrote poetry on mystic, romantic, and religious themes. Her books include Ensayos poéticos (1854) and Ensueños de la mente (1884) (Méndez de la Vega).

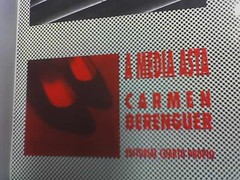

Her sister, Vicenta Laparra de la Cerda (1831-1905) was a poet, playwright, and essayist on the rights of women. With Jesusa, she published several journals. A mother of eight children, Vicenta was known as a singer and soloist, collaborating and performing with other artists for benefit of the Teatro Carrera. She is also known as the creator and founder of the Teatro Nacional in Guatemala. Her political essays in El Ideal resulted in her being forced into exile from Guatemala to Mexico, where she founded a school for girls. Vicenta published books of poems, including Poesia and Tempestades del alma; plays such as “La hija maldita,” “Los lazos del crimen,” and “El ángel caído;” the novel La Calumnía (1894); and other works of history and literary criticism.

The Laparra sisters and Vicenta’s husband went into exile again, from Mexico to El Salvador and Costa Rica, where they continued their commitment to teaching women “self-improvement.” Jesusa and her sister fought not only for the rights of women but for the rights of Native Americans. Though she was partially paralyzed and in a wheelchair for many years, known as “La poetisa cautiva” or ‘The Captive Poetess,’ she continued her careers of writing, teaching, and public speaking (Laparra de la Cerda).

The Laparra sisters’ political and literary circle included María Cruz, Elisa Monge, J. Adelaida Chéves and her sisters, Dolores Montenegro y Méndez, Lola Montenegro, and Carmen P. de Silva. There might be connections between the Laparra sisters and another set of interesting sisters: the Guatemalan poets and editors Jenny, Blanca, and María Granados, who wrote for El Grito del Pueblo and who founded the magazine Espigas Sueltas in 1929.

Many, in fact most, Latin American anthologies and biographical dictionaries that I consulted did not include information on the Laparra sisters despite their extensive international publishing and editing history. A small selection of their verses can be found in Acuña Hernández’s Antología de poetas guatemaltecos (1972).

“La risa” (1884) is written in redondillas, that is, rhymed quartets of octosyllabic lines de arte menor. It describes the emotions behind a laugh of despair and the impossibility of communicating grief and pain in words.

La Risa

Hay una risa sin nombre,

sólo de Dios comprendida

risa sin placer ni vida,

risa de negro dolor;

funeraria, envenenada,

más dolorosa que el llanto,

porque es engañoso manto

donde se oculta el dolor.

Risa que, al salir del labio,

para animar el semblante,

deja una huella punzante

de amargura y sinsabor.

Infeliz desventurado,

es aquel que así se ría,

que esa risa es de agonía,

es de muerte, es de pavor.

Como el esfuerzo supremo

que estremece al moribundo,

al desprenderse del mundo

para nunca más tornar:

dilatada la pupila,

ríe con indiferencia,

despreciando la existencia

que por siempre va a dejar.

Así es la risa funesta

de un corazón desdichado

por un dolor desgarrado

que no se puede arrancar.

Lleva la muerte consigo,

y ríe sin esperanza,

porque nada, nada alcanza

su martirio a disipar.The laugh

There's a laugh that can't be named,

that only God understands;

a laugh without life or joy,

a laugh of black sorrow;

funerary, dripping venom,

more painful than a lament,

because it's a cloak of deceit

to hide pain and grief.

Laugh that, as it leaves your lips

to liven your face,

leaves a heartrending trail

of bitterness and discontent.

Unlucky devil,

that's why you laugh;

it's a laugh of agony,

of death, of terror.

Like the last throes

that shake the dying

when they give up this world

never to return;

eyes open and staring,

you laugh with indifference,

despising an existence

you're leaving forever.

That's how it is: the fatal laugh

of a heart undone

by clawing pain

that can't be rooted out.

You endure your own death,

and you laugh without hope,

because nothing–nothing could match

or dispel your martyrdom.

Photo of Vicenta Laparra de la Cerda – Jesusa’s sister