I have not had any luck in finding many more poems by Lamarque. Maybe I could do it through inter-library loan, or paying someone to xerox or photograph a book in another library for me. I like this poem a lot. Again, am left as a translator knowing that in some places I nail it, or think of an especially graceful & evocative phrase, but in other lines, my elbows are sticking out.

I recommend The Sappho Companion for an excellent description of the history of the idea of “Sappho” & what she meant at different times throughout history, in different countries & languages.

It would be nice to know more about Lamarque’s life, too. There isn’t enough time in the world!

Nydia Lamarque (1906-1982)

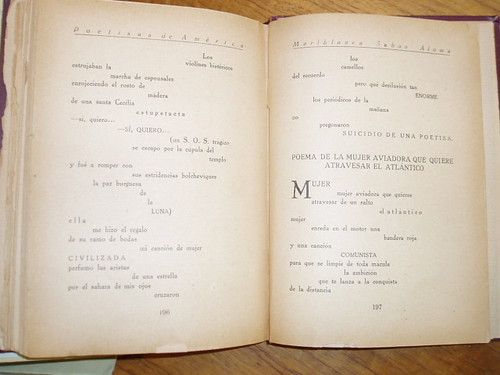

Argentine writer Nydia Lamarque’s first book of poems, Telarañas, was published in 1925, and her second, Elegía del gran amor, in 1927. She was a lawyer and a socialist associated with the vanguardist writers’ group “Boedo.” An officer of the Ateneo Femenino Buenos Aires, Lamarque wrote social and political criticism as well as poetry for newspapers and magazines such as Nosotros and La Nación. Juan Pinto, in Literatura Argentina Contemporanea, calls her “la poetisa de acento más varonil de nuestra literatura” ‘the poetess with the most masculine voice of our literature’ and praises her further for her social conscience and lack of inhibitions (214). She translated Baudelaire, Racine, Rimbaud, Henri De Man, Adolfo Boschot, and Héctor Berlioz. (Maube 287)

“Invocación” summons the ghost of Sappho for an intimate conversation with the poem’s speaker. The myth of Sappho’s frustrated love for Phaon, and Sappho’s leap into the sea from his rejection, dates from the 3rd century BC (Reynolds 71). This legend is also used by Mercedes Matamoros in her poem-cycle “El último amor de Safo”, published in 1902. Lamarque’s rolling cadences invite Sappho to confess her deepest secrets and to describe any part of her love that she found unspeakable. The implication is that only Lamarque can understand and give voice to Sappho’s complaints–because she feels them so deeply herself, perhaps for Sappho’s ghost or for some other person.

Invocación

(A la sombra de Safo)

Ahora hermana lejanísima, ven a mí, háblame con tu boca de siglos.

Ven ahora hermana, que es de noche y vive el silencio.

Nadie a mi lado, nadie oirá nuestro coloquio.

Sólo estará junto a mí el buho fiel del recuerdo.

Mira, las estrellas se dejan caer en el lecho obscuro de la noche,

y para nosotros va a dar marcha atrás el Tiempo.

Me dejarás que llegue hasta tus brazos acogedores;

me dejarás que acerque mi cuerpo tibio a tu marmóreo cuerpo,

y que apoye también la frente calenturienta

para mejor escucharte, sobre tu seno.

Todo me lo dirás entonces al oído, muy bajo,

aunque nadie más que yo habrá de escuchar la voz de tu duelo.

Y me dirás el dolor de la pasión que te ensombreció los instantes,

y la angustia del desamor, flagelante como látigo recio,

y me dirás del hombre aquel en quien concentraste la vida,

por el que tu frente se sumergió en el misterio.

Me dirás si eran sus dos pupilas de ámbar anochecido,

me dirás si era su boca, en la caricia, sabia hasta el tormento;

y si podía en su frente albergarse un pueblo de ideas,

y si toda la sombra nocturna dormía entre su cabello . . .

Y me dirás también qué emoción te agitó la noche aquella,

sobre el desolado promontorio griego,

y si en el momento de la muerte más que nunca lo ansiaste,

y si más que nunca te castigó implacable el recuerdo,

y si más que nunca te agobió la desesperación impotente,

entonces, entre el cielo y el mar, sola en el instante supremo . . .

Y si la salsedumbre de tus lágrimas,

venció en amargor a la balsámica salsedumbre marina,

y si en espíritu lo besaste aun con un beso resumen de besos . . .

Todo me lo dirías ¡oh hermana! aquí en la noche,

muy bajo, mientras nos envuelve el silencio,

ahora, que estoy ya entre tus brazos acogedores;

ahora que está ya mi cuerpo tibio junto a tu marmóreo cuerpo,

ahora que apoyo la frente calenturienta sobre tu seno,

frío como las helénicas ondas que te dieron el reposo eterno.

Invocation

(To the ghost of Sappho)

Come to me, now far distant sister, speak to me with your voice of centuries.

Come now, sister, made of night, alive in silence.

No one at my side, no one will hear our talk.

Only memory, that faithful owl, will be with me.

Look, the stars let their bodies fall into the hidden nest of night,

and for us alone, Time will turn, running backward.

You'll let me come into your welcoming arms,

you'll let me press my warm flesh to your marble body,

so I can rest, too, my fevered brow

to hear you better on your breast.

You'll tell me everything aloud, very low,

though I hear nothing more than the voice of your lament.

And you'll tell me the pain of passion that darkened every second,

and the anguish of being unloved, like the sting of a brutal whip,

and you'll tell me how you focused your life on that man,

the one for whom you drowned your brow in mystery.

You'll tell me if it was his two eyes of dusky amber,

you'll tell me if it was his mouth which you kissed till torment,

and if it was true that his mind harbored a city of ideas,

and if all nocturnal shadow slept in his hair . . .

And you'll tell me also what emotion that shook you, that night,

atop the desolate Greek cliffs,

and if in that moment of death, more than ever, you longed and desired,

and if, more than ever, you were punished by implacable memory,

and if, more than ever, impotent desperation oppressed you,

then, between heaven and sea, alone in that supreme instant . . .

And if the acid salt of your tears

defeated in bitterness the vinegar salt of the sea,

and if in spirit you kissed him with one kiss that summed up all kisses . . .

You'll tell me everything–oh sister!–here in the night,

very low, while silence wraps us round,

now, while I am yet in your welcoming arms;

now, while my warm flesh is pressed to your marble body,

now while I rest my fevered head between your breasts,

cold as the hellenic waves that gave you eternal rest.