I did a lot of trying to say no to things and step down from things I wasn’t doing (well enough, or in some cases, at all) which was kind of my therapy homework and which was very difficult. Why is focusing so difficult? Why can’t we live 6 lives at once??? Why am I getting older and more tired? It just has to be.

More centrally (the therapy part I suppose) What if I didn’t feel like I was somehow failing all the time and disappointing people? I think last time I said this in semi-public a little group of my friends stared at me silently, looked around the table at each other and then one of them as spokesperson explained that when I said things like that with all the things I actually do manage to accomplish, I was insulting them. Like if I thought that harshly of myself, when I had a job, was in grad school, had a toddler, and was still also doing extra projects, then… how was I judging them? Years later I still think of this (thanks elaine) and how helpful it was at giving me a kick in the ass. (Not an instant fix obviously, but a useful insight)

Dealing lots with architects/contractors. There is some little thing every day and a bigger meeting once a week. Construction continues under our house. Someday, someday! we will live in that bit of house, it will all have wheelchair access, I will have a REAL BATH and soak and read in the tub, without the noise of power tools, and I will get to fix up the garden again to enjoy it.

Last week and this week, I’m focusing in on work for DIFxTech and on GOAT. I even got a little help from M. in discussing how to catalogue and tag some of the GOAT archive – how useful to have another librarian in the family! And both kids were here last week and are now back at school while Danny is in Europe till the end of the week.

Annoyingly I not only got a cold (not Covid thankfully) but also got my period for the 2nd time in the past year, resetting my menopause clock so I will still be officially “perimenopause” till at least next January. Mother of God, I was so fucking pissed, it was so great to have it over with, but no. Fuck!!

I took a sewing lesson in the Mission, making a striped velvet zippered throw pillow with fabric that reminded me of one of my grandmother’s couches that had similar colors and how I would lie on it and pet the velvet one way & then the other. Got my sewing machine out resolving to practice on it on some scraps but then realized the pedal was missing which led me to clean out the entire row of cabinets.

Will I actually learn to sew and finally complete the blue jean blanket of my dreams – modeled after that crazy quilt bed cover I slept under once in the 90s at Harry and Daffodil’s house, made of I think Daff’s former lover’s favorite jeans, with all the pockets and rips on top and the underneath soft with the texture of the inside-out frayed bits. It was comfy and comforting and so bittersweet to think of his love for this dead young man and all the ways the radical faerie & other community had come together & was grieving so hard. I have forgotten his name but not the love that whoever made the quilt had for him. I think he must have been an amazing person.

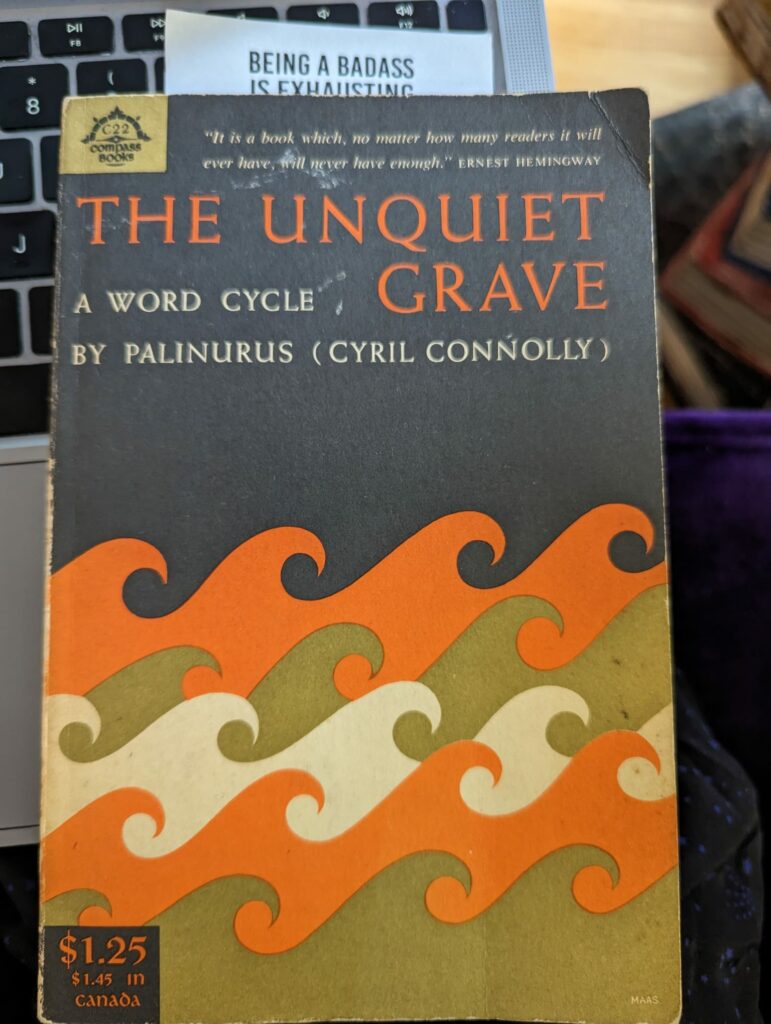

In reading this week and last:

Loved the Christopher Rowe books and short stories, tons of Weird Kentucky, the wonderful Navigating Fox, and I hope maybe there could be more about the detective dog. (Maybe a prequel so we also get the crow friend?)

I also loved Tuf Voyaging, which somehow I have never read. It’s a great read that comes off like light space opera, but which is actually kind of a complicated moral fable. The Portmaster was so interesting – like Martin trying to write in a super valid critique of his too powerful main character and what power does to him – I am always saying this so I warmed to it. It was like seeing him in dialogue with the ghostly hand of feminist science fiction, so I enjoyed that. Plus of course I warmed to the (too powerful) nerd hero and his cats and his (too powerful) spacecraft (as the youth say, he is “a bit acoustic” in a charming way.) Having the down to earth feministsf Portmaster tell him off repeatedly did not stop the OP MC one bit. But she wasn’t treated badly in the story, and she gets some kittens, and she had her own problematic behaviors; I liked how Martin treated her as a character.

Damiano by R.A. MacAvoy. Readble but not my favorite, a little too fetishy of a certain type of anguished christian man that just annoys me. I did like the witch Sara from Fennland for a moment, and then didn’t again (bad boyfriend, whinges too much about age) I also don’t think much of Damiano. Oops I accidentally slaughtered more people with my magic ™ waah waah oh my little doggie is so pure oh also my literal angel who i definitely don’t lust after, wahh wahh but also women are purty. Goth cosplay and a broken lute! The end. (Sorry everyone.)

Very, very, very annoyed by Rome of One’s Own, which I feared was going to annoy me. I had some hope it might be a nice overview, since “forgotten” women of history of basically anywhere and when is one of my very favorite things to read. Maybe I would learn something about women of ancient Rome. BUT NO. It’s so, so bad y’all. The most annoying kind of “history” book.

I want to just blast it with my scorn for a moment but let me set a background first. At best, the book is trying to explain that historical interpretation can change over time. But it fails to make that clear and usually ignores the historical context of it sources. Instead it messily conflates truth, what the authors of those sources (Livy, Ovid, or whoever) thought was true, what later generations thought, or may have thought, was true and how they interpreted a story about a particular woman, and then what the book’s author and apparently, her (British, women) readers will read into that story. Often kind of (and only kind of!) attributing agency, empowerment, or historical importance to the woman in the story.

If you want an example of this done incredibly well, I love how Margaret Reynolds approaches it in The Sappho Companion.

Rome of One’s Own did not do it well. It was like I was nonconsensually shunted into a wine o’clock mumsnet party who were all incoherently yelling “You go, girl!”

Please just go read some primary sources! OMFG!

There could have been a fine book here that clearly outlined, here’s some things that particular writers said about particular women who may or may not have been semi-mythical, and exactly when that was, and what else was going on, and then, what other people in England/Great Britain then said about those women in subsequent centuries and how they reinterpreted things in their own context! And then you could add your own Liberated Ladies perspective onto that but make it clear what you are DOING. you could write a popular audience history book that lays some coherent groundwork and is still readable!

And, only talking about what Livy and Ovid and like 3 other dudes said about some mythical women of Rome’s founding, does a huge disservice to all the cool history of regular people and women’s daily lives that we can look at from the past… century that puts it into actual context including with archeological sources!

Here is where I should recommend something better as an antidote and I do have examples but the first thing that comes to mind is Elizabeth Wayland Barber’s “Women’s Work” and of course Prehistoric Textiles. (Way too broad in scope, not actually Rome, but gives you actual information! that! is! organized!)

I then bounced hard off a detective thriller, Zero Day. It started OK promising a married pen testing duo and a competent hacker heroine and then went quickly to some places I did not want to go: a background of what sounds like violent/life threatening/maybe rapey abuse by her cop ex boyfriend, and her nice hacker husband murdered by chapter 2. I can’t read that shit while D. is out of town! Fuck no!

Not to mention, after the murder, she gets a mysterious email saying that there is a mysterious 1 million dollar life insurance policy and she CLICKS THE PDF IN THE EMAIL.

Nope nope nope! Must we?! NOT going to finish that one. If there is a less violent novel by Ruth Ware, with less dwelling on women’s fear, trauma, and fucking up, please let me know.

To clear my mind of all that, I went on a Project Gutenberg spree and downloaded a lot of dumb Angela Brazil books (The Jolliest Term on Record; Madcap of the School), an equally ridiculous Cherry Ames book, and Clematis by Bertha Browning Cobb which is a lovely book about a neglected orphan and her beloved kitten. And some things off the 19th century list of classic kids’ books. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_children%27s_classic_books that I haven’t read.

So in short, BRB, gonna play some jolly field hockey with my chums and then go back to my digs for tea and spiffing rock cake (wtf is that, i’m still not sure but it does not sound nice). Why is diggings, or digs, school slang for where you live? mining and miners? archaeology? something else?)