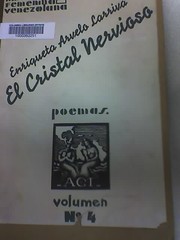

Happy Poetry Month! Today I have been thinking about Enriqueta Arvelo Larriva, a Venezuelan poet from the 20th century (1886-1962). Her poems are small and odd, but huge internally, like a pocket universe captured and studied from all sides; a bit abstract and philosophical. This, at a time when it seems to me like the way to be a famous woman poet was to blaze passionately forth in a sort of meteoric scandal of words. Arvelo Larriva’s positioning of herself is at the same time very personal and connected to the specific landscape of the Venezuelan llanos, the central plains — a tropical prairie. But at the same time she positioned herself as a very abstract, analytical, point of human consciousness.

Arvelo Larriva began writing and publishing around 1920 that I can verify (but I have also read she was a poet beginning at age 17, much earlier). Most of her poems that I’ve translated were published in the 1920s, but I don’t have all the research done to know exactly when they were written.

I’d like to point out a pattern I have found in looking at the work of women poets in Latin America. Their poetry was often being published little by little in journals, the same journals as more famous men who were their peers, who were in their same literary circles. But the men became famous more quickly, had books published earlier. I think this is one reason that books of literary history tend to describe the women as footnotes, afterthoughts, imitators, or as not quite catching the wave of a literary movement. It appears from short biographical notes on Arvelo Larriva that she began publishing in 1939. This is not true — she was publishing as early as 1918, and certainly throughout the 1920s, and was part of the Generación de 1918; and was part of the Vanguard of the 1920s student movement as well.

Why do I care? Well, because histories talk about those movements – but leave her out, or only mention her 20 years after her vital, early work. The elision of 20 or more years of her publishing history means that she is also cut off from politics; her brother and others of her political circle were jailed in the 1920s. She remained in their hometown on the prairies. My feeling is that the story of her life might be quite interesting and complicated, but that complication is not represented in any descriptions I’ve seen — which just marvel at how she could write clever poems even though she lives out in the sticks instead of in the exciting capital.

Her work persistently reminds me of the somewhat better-known poems by David Rosenmann-Taub from the 1950s. I’ll talk about his poems later this month and connect back to this post on Arvelo Larriva. I also think of some of the short airy poems of García Lorca.

So, onward to a few poems. They might not be your cup of tea. But I get very excited over their depth and over how different they are from other poems of the time. They stand out to me. Also, since I have read a bunch of her work, I am able to see some things in a larger context. So if it seems that I am reading too much into a tiny poem, try to bear with me.

Destino

Un oscuro impulso incendió mis bosques

¿Quién me dejó sobre las cenizas?

Andaba el viento sin encuentros.

Emergían ecos mudos no sembrados.

Partieron el cielo pájaros sin nidos.

El último polvo nubló la frontera.

Inquieta y sumisa, me quedé en mi voz.

Destiny

A dark impulse burned up my forests.

Who is left for me from the ashes?

The wind roamed alone, meeting no one.

Echoes emerged, mute, unsown.

Birds without nests divided the skies.

The last dust clouded the frontier.

Anxious and meek, I dwell in my voice.

“Destino” can be read in light of the Venezuelan llanos and the prairie burn-off of the dry season. Yet, like many of her poems, it can be read as a political commentary. There is the “dry season” layer, specific to the geography of Barinas, where she lives; the tangled, thorny groves are burned with controlled fires in order to clear room for new growth for vast herds of cattle. The poem could also work as a personal one about philosophical and spiritual renewal. However, the “pájaros sin nidos” ‘birds without nests’ can also be read as the journalists, students, and poets who had to flee the country under the rule of Juan Vicente Gómez, after the 1927 student uprisings or other political clashes.

The creative act of the word, of poetry, is presented as a solution to the problems posed in “Destino” as in many of her other poems. I see her as writing with intense vitality about violence, revolution, politics. But as encoding those concepts within a sort of personal artistic framework, where the poet’s voice breaks out of everyday life, a jailbreak from reason and order.

To be honest here on my translation, I am not happy with those birds without nests. Well, how long can one stare at the page muttering, “homeless birds… birds without nests… nestless….. no, dammit” before one just goes with whatEVER. Sometimes, I will be driving down the highway and a line of a poem I translated years ago will pop into my head — one of this sort of line, where my English is clumsy and graceless — and the perfect, beautiful phrase will come to me in a flash. From what people say, this happens to all translators and that is why we are always revising. I can work very hard on a translation, and feel in the groove for 90% of it, but that other 10% that just wasn’t inspired, is a torment.

I am also fond of this poem:

Vive una guerra

Vive una guerra no advenida. Guerra

con santo y seña, con la orden del día,

con partes, con palomas mensajeras.

Guerra pujante dentro de las vidas.

No digo en las arterias; más adentro.

Ni un estampido ni un rojor de fuego

ni humo vago dan desnudo indicio.

Mas paz de tiza la refleja entera.

And I will give you the first bit, which I think is interesting to translate. Try it yourself as a challenge, if you like.

A war lives

A war lives, unheralded. War

with saint and sign, with the order of day,

with parts of things, with messenger doves.

War throbbing inside whole lives.

I don’t say in the veins; deeper inside.

“Vive una guerra” continues the internalization of violent metaphors, with war metaphors to represent existential and philosophical struggles.

Someday I would like to really do her poetry justice, and translate her first two books. Just the little bit that I do know about her family (which included many poets) and her life and about Venezuelan politics, history, and geography, illuminates the poems for me. If I could do the original research, find the journals where her work first appeared, read her poems in that context, I imagine that I could translate them better, explain them, present them in a context that would help other people see where the poems lead.

There is more to say about the ways that Arvelo Larriva was framed as a woman, and about the gendering of literary history as it happens and in hindsight. I gue

ss I’ll go into that more in future posts as I talk about other poets and their lives.

What I truly wish for is the ability to get some good, lowdown, dirty gossip. I’d like to know the poets I translate, who have been dead since before I was born, in the same way that I know the poets who are alive now in my city; what do people think of them, really? What are they like? Would I have liked hanging around with Enriqueta? Was she rude, kind, radical, bitchy, boring, pedantic, vindictive, wise? Was she more interesting when she was young? What was the course of her life? With many poets, I do get a sense for the arc of their lives and careers. With Enriqueta, I barely know a thing. And am not likely to get it in this lifetime. Maybe I’ll find an old journal or two, or a letter; her letters with Gabriela Mistral and Juana de Ibarbourou. Just knowing those letters exist, changes everything for me.

Maybe someone who knows more will write a longer Wikipedia entry. More likely, some boorish great-nephew will write to me and go “My god! You’re talking about old Aunt Netty and her insane scribbling! I didn’t think anyone cared about that! Blah blah blah, all those poetry readings, grande dame of Barinitas… She smelled like dusty lavender and dead mice… But, she made good cookies.” I can’t romanticize my dead poets too much, because I always imagine out those great-nephews who have become excellent dentists and who have healthy lives and perspectives lacking in poetry, who knew only the human being and not the metaphysical point in space and time that was the free-floating philosopher poet.

Technorati Tags: poetry