Translation: Mariblanca Sábas Alomá

Mariblanca Sábas Alomá (1901–1983)

Mariblanca Sábas Alomá was an Ultraist feminist Cuban writer. She was involved with the first Congreso Nacional de Mujeres in Havana in 1923. Her work was published in El Cubano Libre, Diario de Cuba, Orto and El Sol in Havana. Sábas Alomá took literature courses in Mexico and also attended Colombia University in New York and Puerto Rico. She travelled throughout South America, worked as a journalist and editor, and was politically active as a communist and feminist.

In Poetisas de América, Sábas Alomá’s contemporary María Monvel, with characteristic blunt opinion, says of her:

Mariblanca comenzó escribiendo versos blancos, soñodores, llenos de ritmo, musicalidad y vulgaridad. Mariblanca cambió de filas, se pulió, se cultivó, y hoy hace campear su estandarte en las filas del más refinado ultraismo. Poeta de las revoluciones, como la uruguaya Blanca Luz Brum, Don Quijote de las ilusiones extremas, Mariblanca se ha convertido como en broma, en una notable poetisa. Es de esperar que cuando aconche un poco su absolutismo izquierdista, Mariblanca será una de las grandes poetisas americanas. (193)

Mariblanca began writing poetry that was pretty, sonorous, full of rhythm, musicality and vulgarity. Mariblanca changed her tune, became refined, cultivated, and today has raised her banner in the ranks of the most savvy ultraists. Poet of revolutions, like the Uruguayan Blanca Luz Brum, a Don Quixote of extreme illusions, Mariblanca has converted herself from a trivial writer into a notable poetess. It’s to be hoped that when her absolutist leftism settles, Mariblanca will be one of the greatest American poetesses.

Sabás Alomá’s 1920 article “Masculinismo, no. Feminismo!” was published recently in a volume of her essays, Feminismo. In 1928 she published an article in which she characterized lesbianism (“garzonismo”) as a crime against nature, encouraged by capitalism, that would disappear with the advent of true socialism; for her, feminism was in complete opposition to lesbianism (Menéndez).

Magda Portal wrote critical articles about the socially engaged vanguardist poetry of Sabas Aloma in a 1928 issue of Repertorio americano, “El nuevo poéma y su orientación hacia una estética económica” (Unruh, Performing, 176).

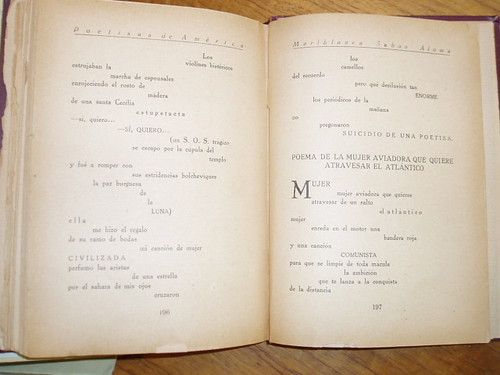

In “Poema a una mujer aviadora,” Sábas Alomá spaces words freely across the page, leaping great distances in sweeping arcs, just as the aviator would zig-zag across the Atlantic. A later poet, the Argentine writer Elvira Hernández, might be paying homage to Sábas Alomá in her long poem “Carta de viaje,” both in form and in theme. Hernández describes a flight across the Atlantic from south to north, from Latin America to Northern Europe, focusing on the dislocated state of flying, not on land, sea, or earth, detatched from terrestrial metaphor.

Juana de Ibarbourou echoes the “shout” of Sabás Alomá in her 1930 poems “El grito,” “Las olas,” and “Atlántico” in which she longs to leap the distance between the world of the real and the world of ideals.

Poema de la mujer aviadora que quiere atravesar el Atlántico

MUJER

mujer aviadora que quieres

atravesar dee un salto

el a t l á n t i c o

mujer

vereda en el motor una

bandera roja

y una canción

COMUNISTA

para que se limpie de toda macula

la ambición

que te lanza a la conquista

de la distancia

enorme

mujer

no asciendas por coqueteria

asciende porque el clamor intenso da

los hombres que sufren

t e p r e s t e s u s a l a s

mujer

tiende sobre la vastedad marina

que

S

E

P

A

R

A

dos continentes

el arco fraternal que una en un mismo

anhelo de

J U S T I C I A

a América

y a

Europa

mujer

desde una altura de 2,000 metros

deja caer sobre el mar

y sobre la tierra

L A N U E V A P A L A B R A

así veremos en la noche

un zig

zag

guiar

d e e s t r e l l a s j u b i l o s a s

mujer

esconde en la cabina de tu aeropleno el

G R I T O

– santo–y–seña de la América joven –

A N T I M P E R I A L I S M O

y clávalo

– para que toda Europa lo contemple

y

los ejércitos de

RUSIA

le hagan los saludos de ordenanza

EN LO MÁS ALTO DE LA TORRE DE EIFFEL

mujer

si tu sueño se rompe en el canto de una ola

no llegues a los dominios de lo

desconocido

rezando–padre nuestro, que estás

en los cielos

–sino regalando el oído

de los proletarios exámines

con un

– ARRIBA LOS POBRES DEL MUNDO

DE PIE LOS ESCLAVOS SIN PAN . . .

Poem of the aviator woman who would cross the Atlantic

WOMAN

woman aviator who wants

to cross in one bound

t h e a t l a n t i c

woman

in the engine falling into step with a

red flag

and a song that's

COMMUNIST

in order to cleanse everything soiled from

the ambition

that throws you at the conquest

of distance

enormous

woman

you don't ascend through coquetry

you ascend because the intense clamor of

people who suffer

l e n d s y o u w i n g s

woman

you stretch above the marine vastness

that

S

E

P

A

R

A

T

E

S

two continents

the fraternal arch that in the same

longing for

JUSTICE

for America

and for

Europe

woman

from a height of 2,000 meters

let fall across the sea

and across the land

T H E N E W W O R D

so that we'll see it in the night

a zig

zag

trail

o f j u b i l a n t c o n s t e l l a t i o n s

woman

hidden in the cabin of your airplane is the

S H O U T

– sacred–and–signal of the young America–

A N T I M P E R I A L I S T

and drive it home

– so that all Europe will see it

and

the multitudes of

RUSSIA

will make their comradely greetings the norm

ON THE HIGHEST PEAK OF THE EIFFEL TOWER

woman

if your dream breaks on the song of a wave

you won't arrive at the domains of what's

undiscovered

praying–our father, who art

in heaven

– not conforming to the rule

of the watchful proletariats

with a

RISE UP, POOR OF THE EARTH

STAND UP, SLAVES WITHOUT BREAD . . .